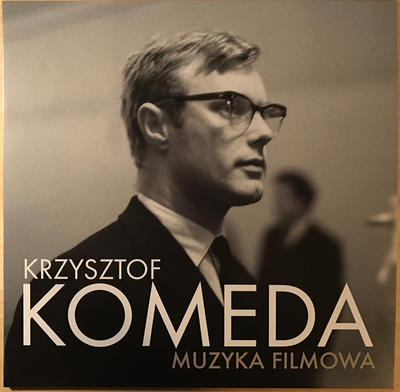

In 1960s Los Angeles, three Polish pals were indulging their creativity within the extreme excesses of the West. After spells in France, West Germany and Israel, the cynical non-conformist writer Marek Hłasko had just arrived in the U.S., under the assistance of director Roman Polański. Polański was, at this point, still a Hollywood darling, working on his soon-to-be critically-acclaimed horror film Rosemary’s Baby (1968). The final figure was Krzysztof Komeda, a jazz pianist and composer who was building a steady reputation for scoring independent films, especially through his ongoing collaboration with Polański. The fate of Polański is well-known in the West; the other two, not so much. I’ll return to Hłasko in a few months time. Today, I tell the story of modern European jazz’s greatest pioneer.

***

Last year, I was sat in a packed-out church hall in East London, listening to jazz from under the Iron Curtain. Self-styled ‘punk jazz’ bassist Wojtek Mazolewski was in full swing with his Gdańsk-based quintet, giving us a radical sermon in Polish jazz, past and present. Early on in the night, the band played one of Komeda’s early compositions, ‘Kattorna’ from the album Astigmatic (1966). The song is based on a theme he wrote for a Swedish film of the same name. It has the feel of a film motif, one that eerily threatens to digress into free improvisation at each turn. The free-wheeling flair of the trumpet and piano seemed to be at odds with the common British understanding of artistic censorship in the Eastern Bloc – it had me hooked.

The next day, I went to a discussion hosted by Lanquidity Records. Co-owners Mateusz Surma and Adrian Magrys both collect vinyl and have a vast collection of original Polish jazz records from the Communist era. I won’t bore you with the details of every musician that I discovered that night. I will, however, tell you that the dissonant wails and haphazard melancholia of Tomasz Stańko’s ‘Cry’ (Music For K, 1970) screamed out at me. Stańko was that same trumpeter from Astigmatic, and Music For K was his dedication to Komeda. If Komeda inspired this sort of emotion in Stańko, I wanted to find out what sort of life the pianist lived…

***

Komeda was a child of the swinging Polish interwar period. Born in Poznań in 1931, he grew up in an affluent Poland that was rediscovering its cultural identity after regaining independence at the end of World War I. Komeda took piano lessons at a young age, with the intention of becoming a talented musician, This ambition was put on hold following the Nazi invasion of Poland and World War II. The war necessitated moving around the country and Komeda spent his youth between the towns of Częstochowa and Ostrów Wielkopolski. He continued to study music theory and practise piano during the war and post-war decade. Nonetheless, he felt that his musical education had been interrupted and returned to Poznań to study medicine, eventually specialising in ear, nose and throat pathologies.

It was during this time that Komeda’s schoolmate Witold Kujawski introduced him to jazz and took him to jam sessions in Kraków. During the 50s, music was still under tight control in communist Poland and jazz musicians held covert ‘catacomb’ sessions in Kujawski’s tiny Kraków flat. The influence of the catacomb era is palpable in Komeda’s early recordings, which are composed in the bebop style of the time. As Komeda began to play more regularly and form his own sextet, his fascination with modern jazz pushed him closer to avant-garde inclinations. It’s no coincidence that this happened in the late 50s, during the cultural thaw that succeeded Stalin’s death. This was a time when the communist Polish state even set up its own record label – Polskie Nagrania Muza – that issued everything from pop to rock and jazz.

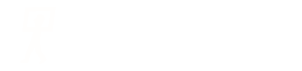

Komeda’s Astigmatic (the unique name perhaps a result of his medical background) was the fifth release on Polskie Nagrania Muza’s jazz imprint. It was recorded a few years after Komeda’s domestic success had granted him license to travel and perform overseas, both within the Eastern Bloc and further afield in Scandinavia and the U.S. At this point, Komeda had already scored and starred in Andrzej Wajda’s early classic Innocent Sorcerers (1960), and his burgeoning relationship with Polanski had led to music credits on Knife in the Water (1962) and Cul-de-sac (1966). Within a few years, he would score Rosemary’s Baby too. That haunting lullaby with Mia Farrow’s melancholic singing? All Komeda’s work.

***

The abrupt end to Komeda’s life was probably about as hazy for him as it is for us. Various accounts exist, but it’s known that in December 1968, Hłasko was hosting a party in LA with Komeda and Polański in attendance. A playful drunken scuffle between Komeda and Hłasko led to the latter accidentally pushing the former off a cliff. The young jazz pianist hit his head, went into a coma and died a few months later after being flown back to Poland.

Like many Polish artistic giants – including Hłasko – Komeda now lies buried at the Powązki cemetery in Warsaw’s Wola district. Unlike the crazed colourful cadences of his music, the man’s grave and inscription is conventionally austere. From Stańko’s 1970 tribute to contemporary jazz septet EABS’s recent interpretation (Repetitions (Letters To Krzysztof Komeda), 2017), Komeda’s cultural legacy continues to inspire musicians across Poland.

Nonetheless, his name is relatively unknown outside of film music nerds and Polish jazz fans. British friends who are jazz musicians tend to look across the Atlantic for their inspiration; a Polish guy I spoke to earlier this month lamented the lack of awareness of Komeda (and his contemporaries) among Polish youth. For my money, he’s the best example of Poland’s vibrant 60s culture and would be a household name in the West, had he not died so young. If you don’t know Komeda, the time is ripe to check out his revolutionary music right now.